POINT OF CONTACT

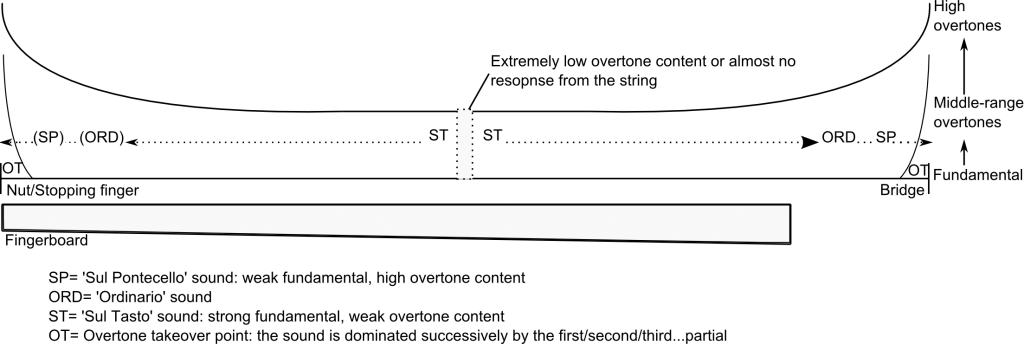

It is well known that a string sound becomes more overtone-rich as contact point moves towards the bridge, sul ponticello, and that there is an area of overtone-weak sound for contact points close to the middle of the string, sul tasto. However, in the context of contemporary music it has become necessary to be more accurate about the relationship between contact point and overtone content.

▶︎OVERTONE CONTENT FOR CONTACT POINTS ACROSS THE STRING LENGTH

The pattern of how the string responds to contact point is symmetrical: ‘sul tasto’ sound is produced around the mid point and ‘sul ponticello’ at both ends.

If a string is excited at its mid point, the contribution from overtones is minimised, producing the most extreme sul tasto timbre. The mid point is half way between bridge and nut for an open string and half way between finger and bridge for a stopped string. As the contact point moves away from the middle of the string, towards either the bridge or the nut, the sound becomes increasingly overtone-rich. Overtone content is maximal for contact points close to the bridge or the nut/stopping finger. The change in timbre as contact moves from the mid point is symmetrical, i.e., symmetrical points at a fixed distance from the bridge or nut/stopping finger are equivalent in tone colour.

This is represented in the following picture. Point A1 is equivalent in overtone content to A2, similarly B1, C1, D1 are equivalent to B2, C2, D2, etc.

▷IN CONTEXT

The literal meanings of sul ponticello and sul tasto can be misleading in the context of contemporary music.

A sul ponticello (literally: on the bridge) sound can be produced over the fingerboard (close to the nut/stopping finger). The terms sul ponticello and sul tasto have come to be indications of sound quality rather than the directions: ‘play close to the bridge’ or ‘play over the fingerboard’. The terms have also been refined, and more exact qualifications of sul ponticello (for example a scale from 1 to 4 from ‘higher partials are emphasised’ to ‘no perceivable fundamental’) are often used.

▶︎RANGE OF CONTRAST IN OVERTONE CONTENT

In some situations, a more sul ponticello sound is possible than in others. This depends on the string qualities

The extremeness of sul ponticello sound depends on the string’s length relative to its width; long, thin strings can produce richer sul ponticello sounds than short, thick strings. This implies that:

- – produce a sul ponticello sound for a high pitch on the C string (short, thick) you have to play much closer to the bridge than for a lower pitch on the A string (long, thin)

- – a fixed contact point on the C string contains fewer overtones than on the G, D and A strings.

The four strings are played ‘sul ponticello’ with a fixed point of contact. The sul ponticello quality has a different character for each successively lower string; the number of higher overtones reduces.

In the case of harmonics, the pattern of ponticello and tasto sound as contact point moves up and down the string becomes increasingly complex for ascending harmonics (see Harmonics).

▶︎OVERTONE TAKEOVER POINT

At a particular contact point, the fundamental becomes weaker than the overtones.

As contact point moves very close to the bridge/nut/stopping finger, higher partials become more present in the sound than the fundamental. Eventually, the fundamental is barely audible or inaudible.

This ‘takeover’ happens in steps: there is a contact area close to the bridge/nut/stopping finger, where pitch is dominated by the first overtone. There is a point closer still where the second, third, fourth… overtone dominates. I call this effect ‘overtone-takeover’.

It is difficult to determine which overtone will predominate, but it is possible to have a certain amount of control over the sound. In the following video a transition can be heard as the lower and then upper overtones dominate the sound.

A demonstration of overtone takeover: a transition from lower to upper overtones is heard as the contact point moves towards the bridge. The transition is shown for the bowed string.

▷TIP

I help encourage the higher overtones here not only by moving towards the bridge but also by increasing bow speed, decreasing bow pressure and tilting the bow.

▶︎IT IS POSSIBLE TO INFLUENCE THE POINT WHERE THE OVERTONE TAKEOVER TAKES PLACE.

The factors that effect where the overtone-takeover process begins are:

- – String length

- – Excitation force (plucking/striking force, bow pressure) and

- – Exciter material/size.

The overtone-takeover point moves towards the middle of the string for:

- – Long string lengths

- – Low excitation force

- – Small, dense plectra/hammers/bows

In other words, the cellist can more easily find areas of overtone takeover and ‘fine tune’ playing to pick out particular overtones if the string is long, excited with low force (or in the case of the bowed string, low bow pressure, high bow speed) and a small, dense plectrum/hammer/bow (in the latter case, tilting the bow is equivalent to reducing width). For example, in the following video, the long string, light bow pressure and tilted bow enable overtone-takeover to take place close to the middle of the string.

The factors that effect where the overtone-takeover process begins are:

- – String length

- – Excitation force (plucking/striking force, bow pressure) and

- – Exciter material/size.

The overtone-takeover point moves towards the middle of the string for:

- – Long string lengths

- – Low excitation force

- – Small, dense plectra/hammers/bows

In other words, the cellist can more easily find areas of overtone takeover and ‘fine tune’ playing to pick out particular overtones if the string is long, excited with low force (or in the case of the bowed string, low bow pressure, high bow speed) and a small, dense plectrum/hammer/bow (in the latter case, tilting the bow is equivalent to reducing width). For example, in the following video, the long string, light bow pressure and tilted bow enable overtone-takeover to take place close to the middle of the string.

The point where overtone takeover occurs can significantly change the quality and harmonic richness of the sound. Towards the middle of the string, the sound is much thinner because fewer upper partials are present.

Examples of overtone takeover at the middle of the string and sul ponticello. Overtone takeover at the middle of the string has a thinner, more flautando sound compared to overtone takeover at the bridge.

▷TIP

For overtone takeover at the middle of the string, I use a ‘Baroque’ bow hold (gripping the bow further away from the frog) to take weight out of the bow.

▶︎A NOTE ON BOWING

The ‘filtering’ of the lower overtones is more easily controlled when bowing the string because, unlike plucking or striking, excitation is continuous; the cellist can make small changes in contact point during excitation to find a particular overtone. High bow speed encourages overtone takeover because it is equivalent to a relative decrease in bow pressure.

▷IN CONTEXT

Controlling overtone takeover is an important technical aspect of contemporary music, useful for producing under/over pressure techniques and multiphonics.

▶︎A NOTE ON PLUCKING

Left-hand pizzicato

If the left hand fingers are being used both to stop and pluck the string, the contact point of the pluck is usually close to the stopping finger and therefore ‘sul ponticello’ in timbre. However, using the thumb to stop the string, or for short string lengths, more flexibility in overtone content is possible.

A tremolo between right and left hands is balanced by playing sul ponticello with the right hand to make a timbre similar to the left-hand pizzicato close to the stopping finger. Firstly, for comparison, an ‘unbalanced’ tremolo is played (the right hand plucks sul tasto) and then a balanced tremolo (the right hand plucks sul ponticello). The tremoli are first played in slow motion and then sped up.

The thumb of the left hand stops the string in a high position and the free finger of the left hand is able to make a sul tasto sound by plucking near to the middle of the string. As the finger moves towards the stopping thumb, the sound becomes more sul ponticello. The lower strings are dampened.

▶︎A NOTE ON STRIKING

Point of contact determines the pitch of the clavichord-type tones and the timbre of the piano-type tones.

▶︎PITCH OF CLAVICHORD TONES

The pitches of clavichord tones are dependent only on the position and the width of the hammer. They are equal when the string is struck at its mid point (i.e., when the mid point of the string coincides with the mid point of the hammer). As the hammer moves towards the bridge, the pitch of the hammer-to-bridge clavichord-type vibration is raised and the pitch of the hammer-to-nut clavichord-type vibration is lowered. This raising/lowering is heard as two pitches moving in contrary motion. If the string is stopped/dampened on one side of the hammer, only one pitch is heard.

The thin followed by the wide edge of a knife strike the string from nut to bridge. The pitches are slightly higher for the wide edge.

▶︎RELATIVE LOUDNESS OF CLAVICHORD TONES

For ‘normal’ battuto, where the hammer jumps quickly from the string, the piano-type pitch and the higher clavichord-type pitch are most present.

If the hammer is held down to the string, the piano-type tone is not heard and the lower clavichord tone is usually louder than the higher. In general, the loudness of clavichord-type tones is proportional to string length, however, contact time between hammer and string also plays an important role in the relative loudness of clavichord-type tones. Cello map link

▶︎▶︎NOTE

For fixed string lengths, hammer-to-bridge tones are slightly louder than hammer-to-nut. Therefore, their amplitudes are not equal at the mid point, but at a short distance from the mid point, towards the bridge.

Psychoacoustic masking can play a significant role in the perception of clavichord-type tones, often concealing the lower pitch completely (especially if it is close to the piano-type pitch).

Examples of col legno battuto: at first the bow stays on the string, emphasising the clavichord-type pitch components, then the bow leaves the string quickly after the strike, emphasising the piano-type pitch components.

▶︎TIMBRE OF CLAVICHORD PITCHES

Contact point also affects the timbre of clavichord-type vibration. As the clavichord pitches become higher (i.e., the length of vibrating string becomes shorter), fewer overtones are present in the sound.

▷IN CONTEXT

It is possible to use contact point to isolate piano-type tones

Very short lengths of string (striking very close to the bridge/nut/stopping fingers) produce overtone-weak and quiet upper clavichord-type tones. In this case, the lower clavichord tone is close in pitch to the piano tone (it is a bit shorter than the total vibrating string length), and therefore is often masked by it; the piano-type pitch is almost isolated in the sound. This can be an effective way of filtering the clavichord pitches from the sound so that only the piano pitch is heard. This might be especially desirable when playing battuto harmonics, which are often dominated by clavichord-type tones.

Stopped string pitches and then harmonics are played battuto sul ponticello and then molto sul ponticello. In both cases, the piano-type pitches are much easier to hear for molto sul ponticello battuti.

▶︎▶︎NOTE

Psychoacoustics probably plays an important role in the ear’s favourable perception of piano pitches. The clavichord pitches might be analysed by the ear as a transient part of the piano-type vibration. This effect is clear when comparing repeated battuto tones with a constant point of contact to repeated battuto tones with slight changes in point of contact. The wandering pitch of the clavichord-type tones in the latter case is tracked by the ear and makes clavichord-type battuto much more easily identifiable than in the former.

Battuti are repeated with constant and then varied contact point. The change in pitch makes the clavichord-type tones seem more present in latter case. The short chromatic scale played in the left hand is less noticeable when the battuti contact points are varied.

▶︎A NOTE ON BOWING

Bowing at the mid point of the string is a special case: almost no pitch is produced.

Bowing at the mid point of a string produces a throaty, inconsistent sound with faint pitch content. Light bow pressure and a fast flautando-like stroke at the point exactly between nut/stopping finger and bridge produce a thin-sounding tone with weak harmonic spectrum. This can sound similar to clarinet or flute timbre. The noise of the bow hairs moving across the string is very present. The following video shows the difference between a heavy, slow bow stroke and a light, fast bow stroke at the mid point.

A heavy, slow bow stroke at the mid point of the string produces a throaty sound. A light, fast bow stroke produces a flute-like timbre. A transition between the two sounds is shown.